A Graze of Glory: Why Good Pasture Matters

IF YOU’RE READING THIS, you’re probably an American that eats meat. If that’s the case, your meat is probably too simple. Or rather, the system that produced your meat is too simple. And this oversimplification causes serious problems for your health and our country’s soils.

Want to enjoy truly healthy meat? Embrace the simple complexity of pasture husbandry.

This may sound counterintuitive. Scripture tells us to live simply. The Righteous Job was a “simple” God-fearing, upright man, the type that the book of Proverbs exhorts us to be. So simplicity is good. Indeed, in all of Steadfast Provisions’ pemmican products, we aim for simplicity. Simple ingredients, processed in simple, traditional ways. But here’s the paradox: to live simply, we must embrace the complexity of God’s creation. Otherwise, things get very complicated, very fast.

This article might be feeling a little complicated, already – but stay with us, and you’ll be rewarded with a new understanding of food, and of how you relate to the natural world around you. All you have to do is understand the story of pasture.

Complex Pastures…

Imagine you’re in a broad grassy field, on a sunny summer day. Before you lies a cow. She’s barely visible amidst the thigh-high grass – only her ears give her away, the ears and the rhythmic sound of her chewing the cud. She’s working quiet magic.

Nearby, a hog nibbles a tuft of clover, and then turns his nose down to the sod, rooting and tooting away.

Seedheads sway gently in the breeze. Songbirds twitter and swoop. A kestrel watches from a fencepost. Time begins to slow down, approaching stillness. If you watch quietly enough, you can almost hear the grass grow. Life abounds.

Simple, right? Wrong.

Natural, yes. Beautiful, yes. Simple? No.

The simplicity is just a surface appearance. Beneath the surface, many complex things are happening, to keep the peaceful growth in balance.

Inside the cow, a community of millions of microscopic creatures works tirelessly to digest fibrous grass. The cow chews once, swallows, and lets these microbes do their work, exuding precise concoctions of acids and enzymes to unlock the precious sugars stored in the grass. Then the cow regurgitates the microbe-worked grass as a wad of cud, chews it again, and swallows it yet again. All in all, it takes about 12 days for a blade of grass to pass through a cow to become either beef or manure.

This complexity continues outside the cow: with every pull of her prehensile tongue, the cow anoints the grass with special enzymes and hormones from her saliva. These chemicals then stimulate rapid regrowth in the grass.

Meanwhile, the grass roots match the length of the above-ground stalks. This means that the root-ends die off with every graze, providing food for thousands of species of tiny bacteria, fungus, and protozoa, teeming invisible beneath the surface of the soil.

All of this activity is affected by the rhythms of the sun, the clouds, and the rain; by irrigation; by the rotational grazing and resting of the pastures; by migratory birds that eat bugs and drop nitrogen-rich manure; by coyotes that eat gophers and other rodents; by vultures that clean up decaying animals; and by pollinator insects that rely on wildflower blossoms.

All of this is, in the words of the Psalmist “Fearfully and wonderfully made.” The miracle of nature is that every part is designed to support and rely on every other part. The complexity of nature results in peace and balance, and its harmony surpasses the bounds of human understanding.

This should inspire nothing but reverence. We should remember God’s words in Job 38: “Where wast thou when I laid the foundations of the earth?… Who hath cleft a channel for the waterflood… to satisfy the waste and desolate ground, and to cause the tender grass to spring forth?”

None other than the Lord Himself.

…Versus Simple Feedlots

But over the last several hundred years, modern human cultures have forgotten to celebrate this complexity, and have forgotten how to work with this harmony. Instead, modernity has sought total control, maximum “efficiency,” and peak “yield,” at the expense of traditional, natural systems of balance. This was essentially a project of simplification:

Take the cows off of the pasture, put them in a feedlot, feed them full of grain, watch them grow faster, and sell more beef. Optimize your system for this one quantitative, profit-obsessed metric.

Engineer the genetics of the corn, breed the cattle for rapid weight gain, and process all the beef in one of a few enormous plants, owned by just three companies. It all seemed so simple… So free from the constraints of God’s creation, with all its mysterious complexities. Here is a system that is homogeneous, able to be duplicated anywhere and scaled up over vast lands and multifarious climates.

But then it all started to go wrong.

Cattle, crowded together in feedlots and eating unnatural amounts of grain, began to get sick with new diseases. So, they began to receive regular antibiotics. Antibiotics contaminate both the meat and the groundwater, causing the development of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and human obesity.

Manure, which is naturally a miraculous fertilizer for healthy soil, becomes overly-concentrated and turns into a toxic mess that poisons rivers and aquifers.

Cattle and other animals suffer in torturous conditions. They are treated like mere machines, rather than part of the creation that we were created to steward.

In fact, the whole living food system began to be treated as a mechanism, devoid of soul, devoid of spirit, devoid of natural variety. Farms became factories, animals became commodities. As the machine grew and more problems arose, everything became so complicated.

This saga teaches us something profound: complexity is not the same as complication.

The harmony of nature is complex. When we attempt to simplify the complexity, we break the balance, and then we try to fix the imbalance with complicated solutions, which themselves create more complications. It’s like if we drink coffee all day, and then we need alcohol to go to sleep, and then we need more coffee the next day to get up, and so on, ever-dependent on more and more complications to compensate for our imbalances.

This cycle is a race to the bottom: lower and lower animal welfare, ecological integrity, deliciousness, and nutritional quality.

The Nutritional Difference

How has this simplification, this industrialization, affected our bodies? In so many ways – mostly by affecting the composition of our favorite ingredient: animal fat. The main differences are in Omega-3s, antioxidants, and Vitamins C, E, and D.

Omega-3 fats are important because they help to regulate inflammation, a process that is healing, in balance, but can cause chronic health problems when there is too much of it. Essentially, if you eat too much Omega-6 and too little Omega-3 fats, your body can be chronically inflamed, which can result in cancer, heart disease, and reduced cognitive capacity.

Grains contain Omega-6 fats, while pasture grasses are rich in Omega-3 fats. So if livestock eats lots of pasture grasses, they’ll get more Omega-3s, and therefore pasture-raised meat causes less chronic inflammation. Omega-3 fat is a highly unstable molecule, which is very susceptible to oxidation and rancidity. This makes fish oil a dicey proposition and increases the value of Omega-3 fats in pasture animal fat, which are protected by the presence of saturated fats.

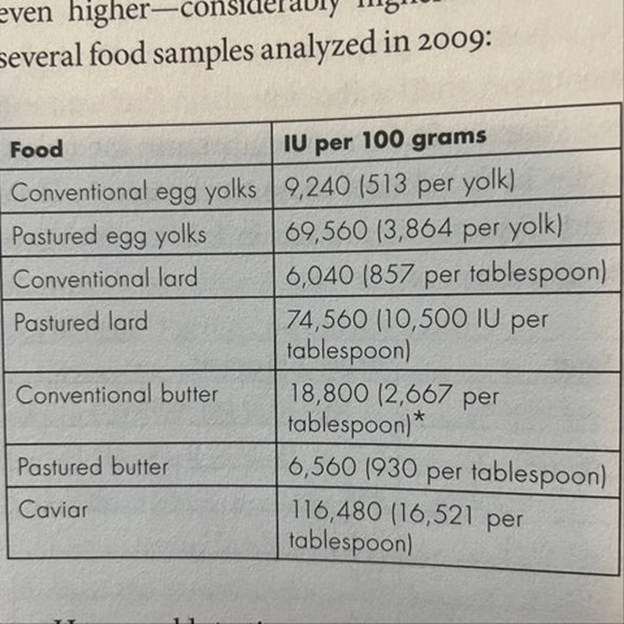

But even more important than omega-3s are the vitamins in the animal fat. Yes, fat contains vitamins, and many vitamins are actually only absorbable in the presence of fat, rather than water. Pasture-raised fat contains much higher levels of Vitamin E and beta carotene, both important antioxidants.

Now, Vitamin D is an interesting case. You probably know that Vitamin D is generally produced due to sunlight exposure. But many of us live in northern climes, where we cannot obtain sun-sourced Vitamin D for about half of the year. This is where pasture pork surely shines (like the sun. Get it?).

Pasture-raised pigs spend lots of time in the sun and absorb the rays through their thin coat of fur. This means they produce lots of Vitamin D, which is stored — you guessed it — in the fat! According to research conducted by the Weston A. Price Foundation, pasture pork lard has 10,500 iu of Vitamin D per tablespoon. That’s an excellent daily dose of D, especially because the Vitamin D in pasture lard comes in the form of calcidiol, the same type as is found naturally in our bloodstreams.

In comparison, factory-farmed lard from sun-starved, pasty pigs only contains about 1/10 the Vitamin D of pasture lard. That won’t get you through the winter!

So modern, simplified, feedlot factory farm meat lacks lots of good nutrients. Even worse, they contain lots of compounds that are bad for you. We already mentioned antibiotics. We should also consider chemical residues of glyphosate and atrazine herbicides, which disrupt your hormones and weaken your intestinal walls, potentially causing food sensitivities and overactive immune systems. You don’t want that in your fat!

It’s pretty clear: nutritionally, environmentally, and morally, modern feedlot animal agriculture is, simply, disastrous. So, what’s the solution?

The Simple Complex Solution

Well, the solution sounds simple: Return to pasture farming. Eat pasture-raised meat.

This is a traditional path in the best sense: returning to pasture isn’t the same as returning to the past. We’ve learned a lot about the true complexity of pasture ecosystems, in the past century, and we have new technologies such as electric fences, soil tests, and targeted mineral supplements. The way we revitalize tradition is to take something older, something more connected to the earth, something that can only work in intimate connection to a specific piece of land, and make it new again.

We’re blowing on a hearth fire that almost went out, adding kindling, resurrecting life in the smoldering coals of ancient wisdom. We are remembering what our wiser ancestors knew: God has made the earth to provide what we need, when we live in a prayerful, humble way, working diligently for what we eat.

We can embrace old ways, with new, appropriate technologies: This is the heart of Steadfast Provisions. We’re part of a movement to rekindle traditional pasture husbandry and food preservation. We take the bounty of natural pasture and concentrate it into a form that can carry you to the top of high mountains.

Meet Steadfast’s Pasture Farm Suppliers

David Treebeard is an Orthodox Christian, organic writer, and creative farmer. His company, Steadfast Provisions, crafts traditional nutrient-dense, nonperishable foods based on pure pastured animal fat.